Second in the series. Link to Bernstein at 100. An appreciation. - the first in a series.

“You compose because you want to somehow summarize in some permanent form your most basic feelings about being alive, to set down... some sort of permanent statement about the way it feels to live now, today.”

“If a literary man puts together two words about music one of them will be wrong.”

“'Is there a meaning to music?' My answer would be, 'Yes.' And 'Can you state in so many words what the meaning is?' My answer to that would be, 'No.'”

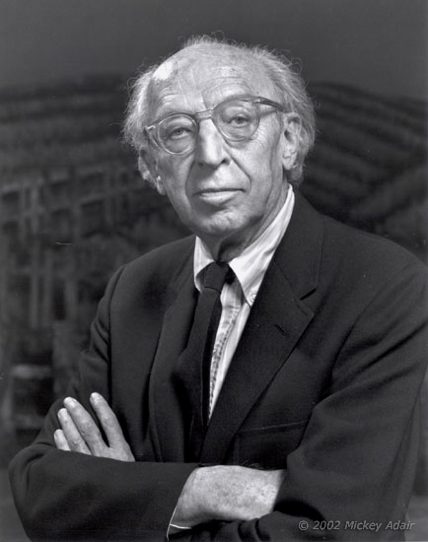

Aaron Copland

Leonard Bernstein first encountered Aaron Copland while he was studying at Harvard. They met at Copland’s birthday party, in 1938. He knew nothing about Copland, who was ten years his senior, but loved his Piano Variations, a particularly difficult piece, and played it at the party. Aaron said, “I wish I could play it like that.” From that point on Lenny would seek advice from Aaron about his own work, and later referred to him as his “only real composition teacher.” They remain close friends for the rest of their lives, and died in the same year, 1990.

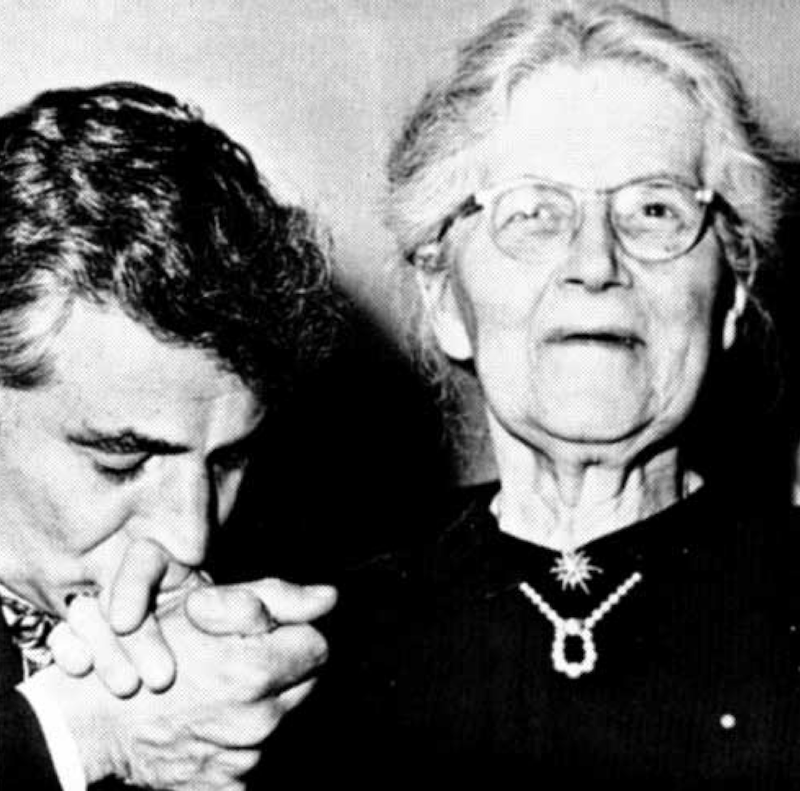

As a young man, Copland went to Paris in 1922, studying with the hugely influential teacher, Nadia Boulanger. He’d only planned to be there for a year, but stayed for three. It was tin Paris that he first met fellow American composers Virgil Thomson, Walter Piston, and Ned Rorem. He was swept up in the heady culture of Paris between the wars, hanging out at Shakespeare & Co. with the likes of Ernest Hemmingway, Gertrude Stein, Pablo Picasso, and Marc Chagall.

After returning to America he wrote in the thorny, modernist style that was expected at the time. But as the Depression approached he became more intellectually and emotionally involved in the socialism that was the rage among the left. By 1933 he began to find ways to make his stark musical language accessible to a surprisingly large number of people. Having encountered the move toward more populist music in Europe, he found a language for American music that reached out to the people. Pieces from the 1930s such as Appalachian Spring, Rodeo, and Fanfare for the Common Man define the American sound better than anything before or since, and have remained part of the repertoire to this day.

Ned Rorem wrote, "Aaron stressed simplicity: Remove, remove, remove what isn't needed...Aaron brought leanness to America, which set the tone for our musical language throughout [World War II]. Thanks to Aaron, American music came into its own."[ Born the son of Russian Jewish immigrants, he was Jewish, but only culturally. He was also gay, but kept it under wraps, as so many had to in those difficult times. He was called before McCarthy’s hearings, but stood firm in his opposition to militarism and the Cold War. When they tried to accuse him of being un-American, the musical community came to his defense. After all, how could the composer of Appalachian Spring be un-American? He defined the very soul of American music.

Later in his life Copland concentrated on conducting, mostly his own music and that of his contemporaries. Ironically, he turned to Lenny for coaching! In 1950, he published his first set of Old American Songs, followed by a second set two years later. (A gay history side-note: the first set was premiered by tenor Peter Pears, accompanied by his life partner, Benjamin Britten.) We sang “The Boatman’s Dance,” from the first set, in 2013, and this spring we’ll be performing three more: “The Dodger (Campaign Song)”, “The Little Horses (Lullaby),” and “Zion’s Walls (Revivalist Song).” Come join us for Lenny & Friends, and hear just how wonderful these songs are!